The History of Indian Tea

Ever wondered how the Indians became addicted to chai?

I’ve been looking for the origins of chai in India, but all I get are legends and references to the British in Assam.

The legends mention a Buddhist monk on his way to China, who noticed people chewing tea leaves. He tried them himself, and eventually brought them back to India. Another legend mentions a Chinese emperor, who 5,000 years ago found a leaf in his pot of boiling water and fell in love with the flavor. Another legend has to do with one of the kings who patronized the Buddhist university of Nalanda, in Bihar, who used it to remain alert during court hours. One more cites Ashoka, saying it was part of his court culture, even though there is no refence to tea in his edicts.

I believe the legends involving Buddhist monks, because tea had been reaching Tibet since more or less since the 7th century via the Tea Roads, a network of caravan trading routes very similar to the Silk Road but much more extensive, starting in Yunnan or Sichuan and taking tea to either Beijing and Russia, Laos and Southeast Asia, Vietnam and Europe, Burma and Bihar, or to India passing through Tibet. The Tibetan branch is called the Tea and Horse Road because it primarily brought tea to Tibet and stout war ponies back to China, though other goods were exchanged like yak pelts, salt, and of course, culture.

I remember that I first heard of this trade road while in Lhasa, becoming so curious that I started toying with the idea of dropping my plan to reach the Taklamakan Desert in order to explore the Silk roads, in lieu of going on a bit of an adventure following one of these ancient tracks. Fortunately, the lack of information dampened my enthusiasm, and I ended up hitchhiking across Tibet and then all around the Taklamakan Desert – an adventure I never regretted.

The Horse and Tea agreement between China and Tibet started around the year 800, and one hundred years later some 20,000 war horses were already being exchanged every year. The trade became so extensive that in the 1500s the Chinese court set up a special bureau to regulate it, establishing a direct correlation between the quality of horses and tea. This led to the production of five different and distinct qualities of tea brick, scored in such a way that they could easily be broken off in equal segments and used like currency. In the year 1661 alone one and half thousand tons of Yunnan tea were sent to Tibet, including the 2,500 kg gifted annually to the Dalai Lama, and the 1,250 Kg destined for the Panchen Lama.

The Horse and Tea agreement between China and Tibet started around the year 800, and one hundred years later some 20,000 war horses were already being exchanged every year. The trade became so extensive that in the 1500s the Chinese court set up a special bureau to regulate it, establishing a direct correlation between the quality of horses and tea. This led to the production of five different and distinct qualities of tea brick, scored in such a way that they could easily be broken off in equal segments and used like currency. In the year 1661 alone one and half thousand tons of Yunnan tea were sent to Tibet, including the 2,500 kg gifted annually to the Dalai Lama, and the 1,250 Kg destined for the Panchen Lama.

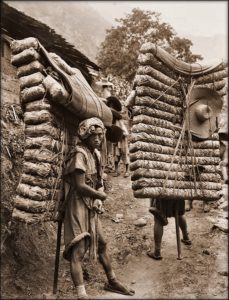

The Sichuan-Lhasa section of this trade route was over 2,300 kilometers long divided into 56 traveling stages, and included 25 suspension bridges made of either rope or iron-chain, 51 river crossings, and 78 mountain passes over 3,000 meters high, making it one of the longest and most difficult caravan roads in the world. Tea was pressed into bricks to reduce space while making loads stackable and well balanced, and was transported by either mules, yaks or people who would carry as much as 100 kg on their backs, all the while singing: “Seven steps up, you have to rest. Eight steps down, you have to rest. Eleven steps flat, you have to rest. You are stupid, it you don’t rest”.

After all this effort, the tea arriving in Tibet tasted very different from the one leaving Yunnan. It absorbed the porter’s sweat during the day, the campfire’s fumes at night, and had to be dried again once it reached Lhasa. This double fermentation process is what makes Tibetan tea special, and the Tibetans have grown so fond of it that the procedure is now replicated artificially.

Whichever way Indians discovered the pleasures of tea, by the middle of the 1500s it was used quite extensively and not only as a brew, as witnessed by a Dutch traveler who noted that the leaves were also eaten as a vegetable cooked with garlic and oil.

As far as Assam is concerned, the British discovered the local tea shrub Camellia Sinensis Assamica only in 1823, after a local Shinghpo chief brought it to the attention of two traveling Englishmen. The Shinghpos had been using tea since at least the 1200s, but as a medicine either brewed or powdered and placed on the skin. Since this variety was more suited to the Indian climate than the Chinese one called C.S. Sinensis, in 1835 they established the first tea plantations as a cheaper alternative to the Chinese variety imported from China.

However, due to all the labour involved, tea remained a luxury enjoyed primarily by the colonisers. It entered the Indian mass market only in the early 1900s, promoted by the British-owned Indian Tea Association. Since black tea was the most expensive ingredient, vendors used milk, sugar, and spices to keep their brews flavorful while holding costs down.

Masala chai gained even more notoriety in the 1950s, when a mechanized form of production lowered the cost while producing a whole new type of tea powder called CTC, which stands for Crush, Tear, Curl – also called Dry Dust. In this method, tea leaves are run through a series of cylindrical rollers with hundreds of sharp teeth that crush, tear, and curl the leaves producing small hard pellets made of tea. Most black tea today is produced using the CTC method which is perfect for tea bags, has a strong flavor, and is quick to infuse.

Masala chai gained even more notoriety in the 1950s, when a mechanized form of production lowered the cost while producing a whole new type of tea powder called CTC, which stands for Crush, Tear, Curl – also called Dry Dust. In this method, tea leaves are run through a series of cylindrical rollers with hundreds of sharp teeth that crush, tear, and curl the leaves producing small hard pellets made of tea. Most black tea today is produced using the CTC method which is perfect for tea bags, has a strong flavor, and is quick to infuse.

Don’t Miss the Next Story!