Dignity in the Face of Adversity

How a beggar taught me an invaluable lesson

Bhubaneswar, 1991

It was evening time, and I was tired from walking through the main shopping district in search of someone who could fix my Walkman. To make matters worse, I was carrying a heavy load: my small dog Afrika safely tucked away in the bag. Six kilos, not a feather.

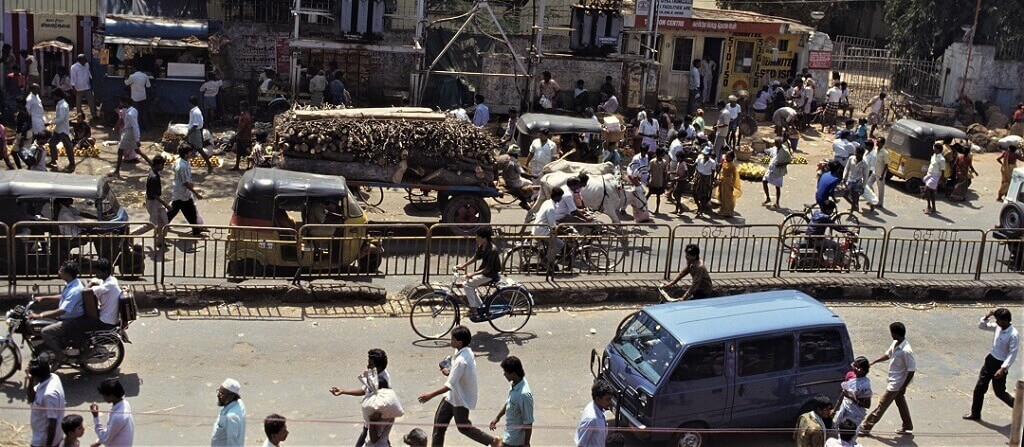

Shops were overcrowded, sidewalks nonexistent, and the traffic was disorderly and intense, with bullock carts, bicycles, scooters, cars, and trucks all mangled together honking their own hand-powered horn. Walking meant overcoming obstacles which became noticeable only at the last minute, from the street vendor sitting next to his wares on the ground, to the hill of sand used to repair a nearby building, the gaping hole left open by the gutter cleaners, a cow squeezing in between the crowds, a large blob of her dung, a mound of garbage, a shop tout stepping in front of my path to grab my attention, or a beggar trying to hold me back while muttering the usual litany.

Plus, the shops. How not to stop here and there attracted by some goods? Orissa was famous for filigree jewelry whose intricate designs often left me agape, and there were patchworked cloths and umbrellas which I thought would look perfect in my garden back home. Looking for the perfect one was not easy, because I had to open them all to see their designs.

Plus, the shops. How not to stop here and there attracted by some goods? Orissa was famous for filigree jewelry whose intricate designs often left me agape, and there were patchworked cloths and umbrellas which I thought would look perfect in my garden back home. Looking for the perfect one was not easy, because I had to open them all to see their designs.

Something else which continuously attracted me were sari cloths. In fact, it was the reason I was there: I had noticed a particularly interesting type of weave and design while walking around the botanical garden in Calcutta, and when I asked the wearer where she found it, she told me it came from Orissa. So here I was, looking to find something similar.

Besides, Sari shops were truly wondrous, the walls covered with tight shelves filled with carefully folded cloths. The modern ones had a long glass counter dividing shopkeeper from client, but most had white-covered mattresses in one corner of the floor where women sat drinking chai while the shop assistants brought them cloths. Since saris are roughly five to nine meters long, and had to be unfolded to see the full design, these mattresses were often covered in hills of colorful material from where emerged the flowers on a woman’s head, or a pair of beautiful eyes.

Unfolding the sari seemed a necessity I never managed to avoid. Most times I just wanted to have a cursory look, and a peek inside the folds would have been enough to decide whether to look further or not. But no! As soon as I touched one shopkeepers would unfurl it in a couple of fast motions, even if there was a mountain to fold from the previous clients, and they had been folding and unfolding saris all day long.

No matter what I said, no matter how I tried to stop it, they picked it up and unfurled it. Part of their duty, I guess, the golden rule of sari shopkeepers transmitted from father to son from time immemorial. And I do mean immemorial, since Indian cloth merchants almost bankrupted the roman empire.

That day I didn’t find a repairman for my Walkman, and I became considerably poorer, having bought a chiffon sari which had nothing to do with my quest, a blue cotton corset to wear under it, and a silver filigree bracelet in a particularly intricate design.

Wanting to get away from the road confusion, I turned into a thinner side street which was as trafficked and full of fumes as the main one, though slightly calmer because the traffic was one-way. There I found a chai shop serving customers on the opposite side of the road, who sat on wooden benches propped against a wall.

I made a sign for the chaiwalla to prepare me a glass, and sat on an empty bench where I placed the bag, opening the zipper for Afrika’s to look around. It was so busy that no one seemed to notice her, which was good, because people liked to ask questions about her and I was in no mood for a chat.

A boy crossed the road to hand the chai over. I lit a cigarette and relaxed, always happy to sit somewhere and look at people, Afrika doing the same with her head popping out the top of the bag.

Then I felt a hand pat my knee.

It was a man without legs, his torso mounted on a piece of wood with four small wheels. He pulled himself around using his hands, one of which was now stretched to ask for money. There were so many crippled beggars in India that it was impossible to give money to everyone, and I was on a tight budget, literally counting my pennies, so I gave him a cigarette. His eyes lit up, and he took one out of my packet with care. I extended the lighter, he drew a puff and, using his hands, parked himself next to me, or rather, below me and to the side.

I never saw someone smoke with so much gusto, flavoring each drag to the fullest before pulling the next. And his posture! Like a king in his own castle, chin up full of pride, spine erect, eyes gazing the passersby as if they were lords in his court. Such a sense of dignity transuded from him, that I never forgot him, his black wavy hair, his light blue tattered shirt, his gazing eyes, the dirty hands.

We smoked together in silence, watching the passersby. He finished the cigarette, wheeled himself in order to face me, gave me a prayer salute, and rolled away.

That was it. No words were spoken, and yet, at least for me, those few minutes were extremely intimate, filled with a strong sense of mutual recognition.

He became my go-to image for when I’m feeling down and out, and need to remind myself about the importance of small things.

Don’t miss the next Story!